The first point is that Einstein was not a Christian. Although he sometimes sounded very

religious in his matter of speaking, especially when he wrote about the wonders of nature, he didn't believe in a personal God. “What I see in Nature is a magnificent structure that we can comprehend very imperfectly, and that must fill a thinking person with a feeling of humility. This is a genuinely religious feeling that has nothing to do with mysticism. (...) I am a deeply religious nonbeliever,” he wrote. Dawkins defines this kind of “religion” an Einsteinian religion and clearly distinguishes it from the Christian belief in a supernatural God. Although Einstein uses the word “God” a lot, it's more in a metaphoric way as a poetic synonym for the laws of the universe.

religious in his matter of speaking, especially when he wrote about the wonders of nature, he didn't believe in a personal God. “What I see in Nature is a magnificent structure that we can comprehend very imperfectly, and that must fill a thinking person with a feeling of humility. This is a genuinely religious feeling that has nothing to do with mysticism. (...) I am a deeply religious nonbeliever,” he wrote. Dawkins defines this kind of “religion” an Einsteinian religion and clearly distinguishes it from the Christian belief in a supernatural God. Although Einstein uses the word “God” a lot, it's more in a metaphoric way as a poetic synonym for the laws of the universe.Then we come to the following point: It's not any kind of God-belief that Dawkins wants to criticize in this book. “I am calling only supernatural gods delusional”, he writes. It's not the Einsteinian “God” he's after, but the God of the Old Testament (Yahweh, that can be found in both Judaism, Christianity and Islam) that is the subject of this book.

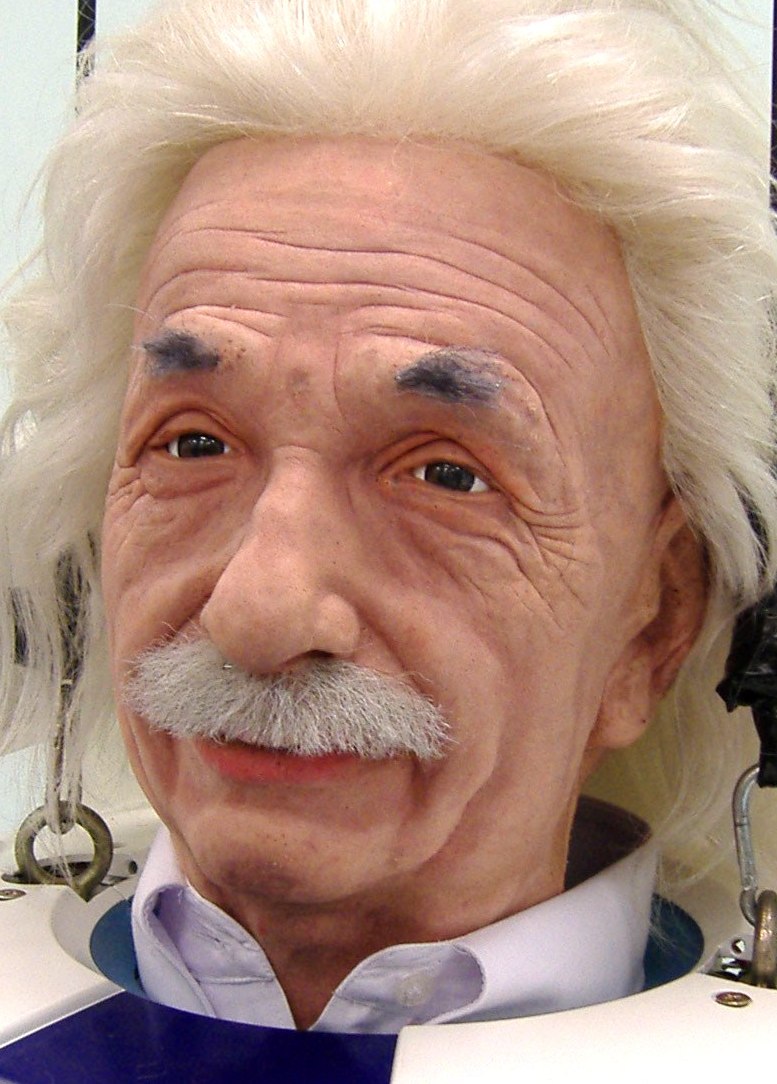

Good to know, because that's actually the God I claim to exist, and I really don't believe in non-supernatural, man-made gods, nor do I believe in God as a non-personal spiritual force hovering around somewhere. I believe in an intelligence, in a creative God with identity, and I'm very aware of that this might sound very human-like to you readers (you

probably picture yourself an old man with long, white beard sitting on his throne in his sky palace with a judging scepter in his hand pointing towards us). But this intelligent, creative, personal God that I believe in, is also a God beyond our imagination, but unfortunately I can only describe him by human categories, because I myself am a human and not a god! So please don't mistake me for believing in this God-picture you probably have seen on a painting somewhere (if God has a human shape, I would guess he looks more like the God character in the Jim Carrey-movie “Bruce Almighty”!!).

probably picture yourself an old man with long, white beard sitting on his throne in his sky palace with a judging scepter in his hand pointing towards us). But this intelligent, creative, personal God that I believe in, is also a God beyond our imagination, but unfortunately I can only describe him by human categories, because I myself am a human and not a god! So please don't mistake me for believing in this God-picture you probably have seen on a painting somewhere (if God has a human shape, I would guess he looks more like the God character in the Jim Carrey-movie “Bruce Almighty”!!).

One thing that irritates Dawkins, is that religion seems to be protected by too much respect, so that it's difficult to have an open debate on existential questions and express opinions about who created the universe on the same level as we debate politics and have meanings about wether Macintosh is better than PC (also a very touchy debate, for that sake!).

Well, first, I don't recognize myself and my surroundings in Dawkins description of this respect for holy things, probably because I come from a more secularized land than him? But anyway, I would say that we probably shouldn't debate existential questions in quite the same way as we debate politics (because I'm really not very found of populistic debate techniques and sarcastic tones in public discussions – and somehow this book has a slightly touch of that as well). But I totally agree with Dawkins that Christianity should be challenged and spoken about in a rational way – because although this God of mine is supernatural and really difficult to put into a box, He's also created us with a brain and the ability of thinking – and also the ability of finding out wether he exists or not and to interact with him and concretely be able to perceive him in our lives. So as much as I am willing to discuss the fact that I have a life in Germany parallel to the one back home in Norway (although you can not see it and really just have to take my word on it) – then I am also willing to discuss the invisible reality, because that's not a fact that I can separate from my normal life. It's actually easier to separate my life in Norway with the one in Germany, because those are going on in two different places and not even at the same time, but my life with God happens right now and has certainly a lot to do with my real life here and now!

So, that was chapter one – and the next chapter (with more exclusive comments from Fräulein Claussen) is just around the corner!

Ingen kommentarer:

Legg inn en kommentar